Human Rights Watch battling to keep potential evidence secret in US Rwandan genocide case

Wichita (Kansas) ďż˝ Human Rights Watch and a former researcher are in a U.S. court battling against being forced to reveal information that could help the defense of a Rwandan elderly accused of Genocide in the U.S state of Kansas. And the defense team reports that it is also having difficulty finding witnesses.

The rights group is arguing their research notes and informants’ identities are protected by the First Amendment and reporters’ news gathering privileges, which are enshrined in the U.S constitution.

The international human-rights organization filed a motion on April 5 seeking to quash subpoenas issued to it and Timothy Longman, the former director of its field office in Rwanda. Longman, now director of Boston University’s African Studies Center, is the government’s expert witness on Rwanda in the Kansas case.

Elderly Lazare Kobagaya is charged in federal court in Wichita (Kansas) with fraud and unlawfully obtaining U.S. citizenship in 2006. The government has said its prosecution of Kobagaya is believed to be the first in the U.S. involving proof of genocide. His trial is set for Oct. 12. He faces deportation if convicted.

An estimated 500,000 to 800,000 people were killed in ethnic violence in Rwanda between April and July 1994.

The Justice Department alleges in its 2009 indictment that Kobagaya lied during naturalization proceedings in Wichita, claiming he lived in Burundi from 1993 to 1995. It claims he was in Rwanda in 1994 and participated in the slaughter of hundreds of people.

The subpoena issued to Human Rights Watch seeks research done for a 1999 report, “Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda,” including a chapter on Nyakizu, Rwanda, where some of Kobagaya’s alleged crimes occurred. The subpoena sent to Longman also seeks any additional material relating to his expert testimony.

Longman is testifying about background matters relating to the genocide in Rwanda and Nyakizu, not about anything specifically involving Kobagaya, HRW spokeswoman Emma Daly told AP in an e-mail. The organization contends confidential sources are indispensable to its newsgathering and reports and are protected by reporter’s privilege and the First Amendment.

“We believe that disclosing Human Rights Watch’s confidential sources would subject them to the risk of reprisals and persecution,” she said.

Kobagaya’s lawyer Kurt Kerns says Human Rights Watch’s concerns are misplaced and he has no interest in putting anyone at risk but wants to ensure his client gets a fair trial.

The organization interviewed people in Nyakizu shortly after the genocide with the stated purpose of bringing those responsible to justice, Kerns said in an e-mail. The group is quick to provide prosecutors with information pointing to people’s guilt, but in this case it has evidence supporting Kobagaya’s innocence, he said.

“HRW should be interested in holding those who commit international crimes accountable, but it also needs to be equally interested in making sure those who are innocent are not falsely accused,” Kerns said.

The Justice Department declined to comment on the pending litigation.

Meanwhile, in a related development, Mr. Kobagaya�s lawyer reports that he is having trouble finding witnesses to testify for his client. See : 83-year-old Rwandan Lazare Kobagaya in Wichita (Kansas) court as genocide suspect

April 12, 2010 No Comments

83-year-old Rwandan Lazare Kobagaya in Wichita (Kansas) court as genocide suspect

Wichita (Kansas) – Lawyer Kurt Kerns found himself traipsing through some of the most dangerous, politically torn parts of Africa looking for witnesses in a criminal case back in Wichita. “I was walking through the Congo, and I realized I’m the only white guy on the street in a place the State Department warns Americans shouldn’t be traveling,” Kerns said. “But what do you do? You have to go where the witnesses are.”

Trekking through Tanzania, Congo and Burundi, Kerns tried to recount what happened more than 15 years earlier for the defense of a man facing trial in Wichita, accused of genocide in Rwanda and ordering the deaths of hundreds of people.

Federal prosecutors say the case of 83-year-old Lazare Kobagaya is one of the first criminal prosecutions of its kind on U.S. soil.

Kobagaya’s family in Kansas were shocked when the allegations surfaced in 2009.

“The family, of course, went from anger to surprise to all the emotions you can think of,” said Andre Kandy, a Wichita dentist, of the charges against his father. “We all know our father as a righteous man. To be accused of that level of violence, on such bogus charges, you can understand our feelings.”

Prosecutors say Kobagaya unlawfully obtained U.S. citizenship three years ago in Wichita by lying on government forms about living in Rwanda during the slaughter of more than a half-million people.

That sent Kerns to the other side of the world in a case he estimates has surpassed $1 million in expenses for both sides combined.

Dangerous testimony

Such cases can be treacherous for lawyers and witnesses, Kerns said, due to continued political strife in Africa.

Last week, Human Rights Watch fought to keep from turning over information identifying witnesses to Kerns.

The group’s lawyers said witnesses for the prosecution and defense in genocide trials in Rwanda have been beaten, harassed and charged with crimes because of their testimony.

“This pattern of violence and harassment has continued unabated and has victimized a sizable number of potential or real witnesses,” the legal brief said.

Kerns said Kobagaya’s testimony on behalf of a former neighbor being prosecuted in Finland for genocide led to the current charges in the U.S.

“For 15 years, this guy’s not on anyone’s radar,” Kerns said.

Prosecutors say Kobagaya ordered the deaths of hundreds of people in the Nyakizu region of the southern Rwanda.

An estimated 500,000 to 800,000 people were killed during 100 days of ethnic attacks from April to July 1994. Members of the Hutu ethnic group slaughtered those of Tutsi heritage.

Christina Giffin of the Department of Justice’s Office of Special Investigations said in court filings that this is likely the first criminal case in the U.S. involving genocide.

The Department of Justice declined to comment for this story.

Fleeing violence

Kerns said most of the witnesses he found during the past year still lived in United Nations refugee camps after fleeing to neighboring countries.

“It’s sad, because 15 years later, they are still refugees,” he said.

Kobagaya lived in one of the those refugee camps, his son said, before he moved to Kansas four years ago. Kobagaya currently lives with a son in Topeka, awaiting trial.

For years, Kobagaya’s name wasn’t among thousands of records that have been collected from the Rwandan genocide, Kerns said.

Kerns went to the headquarters of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, which he said keeps a database of about 12,000 interviews taken following the 1994 killings.

“Nobody mentions his name,” Kerns said.

Kobagaya’s name did not appear among dozens of cases being prosecuted by the tribunal, Kerns said.

The Finland interview

Then the Finnish government charged a former Baptist minister, Francois Bazaramba, with crimes against humanity in 2007.

Bazaramba is accused of planning and carrying out the deaths of 5,000 Tutsis. He sought asylum in Finland in 2003.

Finnish authorities are trying Bazaramba, saying he could not get a fair trial if sent back to Rwanda.

Kerns said Bazaramba’s lawyer came to the U.S. to interview Bazaramba’s former neighbors from Rwanda.

Kobagaya said he didn’t know Bazaramba participated in the genocide, Kerns said. Kobagaya gave video testimony in Bazaramba’s defense.

“Then all of the sudden, he became a bad guy, too,” Kerns said. “His name didn’t come up until he gave that interview.”

Kerns said such actions have stifled attempts to find people willing to testify for Kobagaya.

Rwandans “are a country in dictatorship,” Kerns said. “They don’t have a First Amendment, so they can’t say what they want to say.”

In its fight against turning over information to the defense, Human Rights Watch lawyers said last week that one person the group interviewed in Rwanda in 2008 received a phone threat after the interview.

“We have not seen the witness again after the threat,” the group said in its legal filings.

Still, Kerns said he’s found witnesses willing to testify in Kobagaya’s defense.

No subpoena power

Bringing them back is another matter. Kerns said the U.S. has no subpoena powers outside its borders.

That’s one reason Kerns said he’s filed a request to have the case dismissed.

“In this country, you have a right to a defense and can compel people to testify, even if they don’t want to,” Kerns said. “But in this case, we can’t subpoena witnesses because they’re in Africa. That’s why we think this is unconstitutional.”

This is not Kerns’ first case involving potential war crimes.

He is one of only about two dozen U.S. lawyers who practice before the International War Crimes Tribunal in the Netherlands. In 2003, Kerns represented a Croatian commander charged with the torture of Bosnians a decade before.

Prosecutors in the current case say their witnesses tell them Kobagaya worked with Bazaramba in planning and carrying through the killings.

“Several characterize him as a leader of the genocide, acting in concert with other powerful men in the community to ensure that the Tutsi population of the area did not escape violence,” U.S. authorities said in a letter to the Finnish government requesting records from its case.

“The witnesses allege that Kobagaya incited others to commit arson, assault and murder by directing people to commit those acts and threatening those who tried to decline to participate,” the letter said.

The U.S. has no criminal jurisdiction over crimes committed abroad, but it can prosecute someone for lying on a naturalization form, which specifically asks applicants if they have participated in genocide.

Prosecutors say Kobagaya lied on immigration and citizenship documents, saying he had moved from Rwanda to Burundi in 1994. He also checked a box saying he had not participated in genocide.

If convicted, Kobagaya faces deportation.

‘Lived by the Bible’

Kobagaya’s son in Wichita said those accusations don’t reflect the father he knows ďż˝ a gentle man who loves gardening and was devoutly religious.

“He has always lived by the Bible,” said Andre Kandy. “He loves his church. Even when he lived in refugee camps, he had to go to church.”

In Wichita, Kobagaya attended Immanuel Baptist church, Kandy said.

Kobagaya faces trial in October in federal court in Wichita.

“We are looking forward to taking this case into the justice system,” Kandy said, “so we can clear our father’s name.”

The Wichita Eagle.

April 12, 2010 No Comments

Rwanda: Court refuses bail for opposition politician Deo Mushayidi

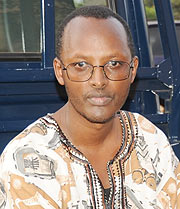

Deogratias Mushayidi, Political Opponent

Kigali: Opposition politician Deogratias Mushayidi, head of the PDP-Imanzi party of exiled politicians, cannot be granted bail, court ruled on Monday � backing the prosecution�s argument that he would temper with crucial evidence and witnesses if released.

The Nyarugenge Intermediate Court ruled that Mr. Mushayidi stay in jail for the 30 days which were requested by prosecution as investigations continue.

Mr Mushayidi was arrested in Tanzania early March and was handed to Burundian authorities which hurriedly extradited him to Kigali within three days.

He is charged with six counts including terrorism, negating the Tutsi Genocide and using forged documents.

Last week, defense attorney Protais Mutembe made a new application for bail.

Despite pleas by the defense for bail to allow Mr. Mushayidi prepare his defense, the Nyarugenge Intermediate Court dismissed all the arguments � saying also that Mushayidi�s past record was ground enough to be denied bail. He is said to have fled the country in 2002 as other unknown charges were being worked out.

The smiling and calm-looking Mushayidi – dressed in the prisons pink clothing – and his lawyers responded in disbelief as the judge ruled.

He was immediately driven back to the Kigali maximum security prison known as �1930�.

April 12, 2010 No Comments

Rwanda: General Marcel Gatsinzi back in Cabinet as Minister for Refugees and Disaster Preparedness

Gen Marcel Gatsinzi, Minister for Refugees and Disaster Preparedness

Gen Marcel Gatsinzi, Minister for Refugees and Disaster PreparednessKigali – Just two days out of cabinet, President Paul Kagame has again appointed ex-Defense Minister General Marcel Gatsinzi to head a newly created ministry.

According to a statement signed by Prime Minister Bernard Makuza, Gen. Gatsinzi, who had been serving on the defense portfolio since 2002, is now Minister for Refugees and Disaster Preparedness.

Gen. Gatsinzi was Saturday evening removed from the powerful defense ministry, and replaced by Gen. James Kabarebe ďż˝ who was the Chief of Defense Staff.

April 12, 2010 No Comments

Rwanda: ďż˝Wa nterahamwe we!!ďż˝: Agony of being fathered by “interahamwe”

Kigali: Rejected, banished, deliberately isolated and even hidden from public view ďż˝ is the indescribable agony of thousands of children born from women gruesomely raped by rampaging interahamwe militia during the 1994 Tutsi Genocide. In this special report, it is discovered for the first time how some 5,000 women raped by the interahamwe, and the children they gave birth, are reclusively living on ďż˝ 16 years after the mass slaughter.

Alivera was already a widow and mother of five when the Genocide started. She conceived from gang rape by the militias. Amid an outpouring of emotion, Alivera narrates that the pregnancy started appearing after the war and killings had stopped. That would mark the beginning of her suffering, as the country was recovering.

The pain is so much and fresh that some of the women do not want to reveal the sex and names of the children so they are not noticed. Alivera often called her son �wa giterahamwe we�, out of anger whenever the boy messed up, even the slightest. The boy hated school, become hostile, and could at times flee from home just to stay away from the mother, family, age-mates and surroundings.

Alivera�s family banished her with her now six children, branding her a prostitute who was forgetting the existing children and continuing to make more babies. The societal rejection left the whole family with nowhere to live, leaving them wandering from place to another looking for even food.

For Claudine, in a rare posture, her daughter ďż˝ who was actually her first birth, was apparently born with her hand touching the chick. Strange! But it happened, and that has haunted Claudine up to today. The still-youthful Claudine attempted suicide several times during the pregnancy she completely disliked. All the families she lived with forced her to abort, or abandon the daughter after she was born.

During the low moments in their relationship over the years, Claudine narrates how the daughter started demanding to know her father. Moved with grief because she had no answers for her daughter, Claudine became brutally hostile ďż˝ at which point ďż˝ the girl would flee to hide, and strangely still, put her hand on her chick ďż˝ in the same style as she was born!

Claudine was so young when she got pregnant that she only knew about it after people started bombarding her with demeaning comments. At some point before birth, Claudine worked as a maid for a family which would make her carry up to 40kg of beans � which are almost her size. �All the families I lived with hated me, grabbed everything from me. I was their slave,� she softly narrates.

At the Kabgayi hospital (southern Rwanda) where Claudine gave birth, white nurses and visitors convinced her to let them take the baby away. She refused, preferring not to allow the baby go without even having developed full sight to notice her mother.

In the case of Mukeshimana, the only person in her whole family and friends who understood her plight was her brother ďż˝ who was a soldier. He gave her money for all the child-birth necessities to flee from Kigali for Byumba (north eastern Rwanda).

Among the men who one-after-another raped Mukeshimana was a gendarme who actually called in others as the rape continued over time. What is so moving about her pregnancy and subsequent birth was that she was considered an outcast, as everybody wanted her to abort the baby.

Due to the hate the child went through, he became so violent, according the mother. By the age of 8, the boy would apparently fight to the point no family wanted him near their children. In school, he would beat up his classmates that no teacher wanted him in their class. Mukeshimana says she noticed the gendarme who raped her after the end of the conflict and is now in jail.

Indifferent from the other such women being supported by a local organization SEVOTA, who still have so much difficulty to come to terms with their painful past, Mukeshimana speaks joyfully ďż˝ even referring to the son as her best friend.

SEVOTA was founded in December 1995 by Ms. Godelieve Mukasarasi ďż˝ herself a Genocide widow. The idea arose following a research which showed that between 3000 and 5000 women were living with in silence and unspeakable pain. Mukasarasi says she was moved when the women complained that so much research has been done about them but nothing was coming back in form of support.

The widowed women and orphans wanted a place they could meet – where, at first, they came together to cry together. Sixteen years down the road, the organization ďż˝ through counseling, material support and outright care, has reunited the widows with their unwanted children.

The children, all of who are now fifteen, are in school, but all share one common situation. At their age, they should be in high school, but are all still at the primary level ďż˝ due to the fact that all have had learning difficulties; they could not stay in school; were often reminded by their peers how their fathers were interahamwe.

For example, Mukeshimana�s son would bitterly complain to the mother why people continued to call him �wa nterahamwe we� � an indication he did not know the history of his situation. He now knows it all and says so be it. At least all the women say they have used this description on their children out of spontaneous anger, calling the females as �wa nterahamwekazi we�.

Through what SEVOTA has termed the FORUM, the widows have a place to meet. Through outings to places like Kibuye ďż˝ with the whole group, which took time to work out, the children came to realize they were not alone, and have accepted who they were.

For Uwera, 16, she has decided to forget everything about her past. �I don�t want to remember anything like that because that is how it is�so what?� she says.

In the midst of the grim picture, these children seem to want to look forward. They want to be considered like very other child at their age. And, as a show that they have moved on, they have dreams. Big dream!!

As for Didier, he loves English football club Manchester United, and is particularly fond of its forward Wayne Rooney. All Didier wants to be is a great footballer like Rooney.

But something still out there: some women have refused to come out with their ordeal because they are too frightened. Some have remarried, and cannot imagine their husbands knowing they were raped by interahamwe. Some widows have deliberately chosen not to live with their sons and daughters – hiding them far away.

And by the way, Jean Paul, 15, wants to be a journalist.

[ARI-RNA]

This story is based on a BBC radio documentary broadcast Saturday April 10, 2010, to mark the 16th Anniversary of the Tutsi massacres. The names in the story are not real, on the request of the people concerned. The documentary is in Kinyarwanda and can be found online on http://www.bbc.co.uk/mediaselector/check/greatlakes/meta/tx/greatlakes_0530?size=au&bgc=003399&lang=rw&nbram=1&nbwm=1

April 12, 2010 No Comments