Posts from — September 2012

Zimbabwe police seek Rwandan fugitive Protais Mpiranya

Zimbabwe’s police say they have launched a manhunt for a former top Rwandan official, accused of taking part in the 1994 genocide.

Protais Mpiranya was a commander in the Presidential Guard in 1994 and is accused of playing a key role in the slaughter of 800,000 ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

Zimbabwe has previously been accused of sheltering him.

The UN’s Rwandan war crimes tribunal has offered a $5m reward for him.

“We want him dead or alive. We are looking for information to arrest him; we don’t know how long he has been in the country,” chief superintendent Peter Magwenzi of the police homicide section told the AFP news agency.

Last year, Zimbabwean official denied that he was in the country.

Source: BBC News

September 20, 2012 No Comments

Rwanda Green leader hopes to register political party

KIGALI � The leader of Rwanda’s Democratic Green Party, who returned from exile earlier this month, said Tuesday he hoped to register his party in time for the September 2013 parliamentary elections.

Frank Habineza left Rwanda for Sweden two years ago after his party failed to get permission to register for the 2010 presidential poll and after his deputy was found decapitated weeks before the vote.

“I had to go because my party was not legal … my partners were demoralized, very scared, so it was not a good time for continuing politics”, Habineza told AFP in an interview.

He said he hoped to get the green light from the government to organise a party congress — a mandatory step in the procedure to register a party — on November 16.

He hopes to have registered his party by the end of December.

The last party congress organised by the Greens in October 2009 was broken up by a man Habineza identified at the time on the party website as “an ex-soldier and a former employee of military intelligence,” along with three accomplices. He said the incident was “a well planned sabotage done by security operatives.”

Habineza on Tuesday however told AFP he “doesn’t know” who broke up the 2009 congress.

After the 2009 congress was disrupted, the government refused to allow the party, created earlier that year by former members of the ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front, to hold a further meeting, he told AFP.

In July 2010 Habineza’s deputy Andre Kagwa Rwisereka disappeared in the south of the country. His decapitated body was found the next day. Two days later a man was arrested on suspicion of his murder, only to be released five days later after the start of the presidential election campaigns.

Habineza says he wants to look to the future and that if he manages to register the Green Party he “cannot fail” to get a seat in parliament.

Source: AFP

September 19, 2012 No Comments

Congo calls for embargo on Rwandan minerals

* Congo accuses Rwanda of funding revolt in country’s east

KINSHASA, Sept 18�(Reuters) – The Democratic Republic of Congo is seeking an embargo on trade in minerals from Rwanda, which it accuses of funding a rebellion in the country’s east, according to a letter written by the mines minister and seen by Reuters on Tuesday.

Tensions between the neighbouring central African countries have risen sharply this year over allegations made by U.N. experts that Rwanda is supporting the uprising in the Congolese province of North Kivu, charges denied by Kigali.

In a letter dated Aug. 29 to Mary Shapiro, president of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Congo’s mines minister accused Rwanda of helping armed groups smuggle minerals out of Congo and into Rwanda for export.

“To put an end to this situation, one of the solutions would be to impose an embargo on all minerals coming from Rwanda, until the establishment of a lasting peace in the provinces of North and South Kivu,” Martin Kabwelulu said in the letter.

“It is in this context that your institution … is invited to instruct all American companies … to no longer buy minerals extracted and/or coming from Rwanda,” he said.

An official at the SEC, which has no jurisdiction to impose trade embargoes, said he was not aware of the letter.

Kabwelulu wrote another letter on the same date to ITRI, a British-based tin industry organisation, calling on it to suspend its work helping to monitor certification of conflict-free tin in Rwanda.

An official at ITRI said it was consulting partners on the matter and would respond directly to Congo’s mines ministry “in due course”.

TRACEABILITY SOUGHT

The Rwandan government did not respond to emails and telephone calls asking for comment on Tuesday but it has repeatedly pledged to clean up its mineral sector and support new traceability initiatives.

Rights groups have long said that illegal exploitation of Congolese minerals such as tin, tungsten, tantalum and gold has helped fuel nearly two decades of conflict in the east of the vast country that has left millions dead.

There has been growing international focus on efforts to tackle so-called “conflict minerals” and last month the SEC confirmed rules which will require U.S. companies buying minerals from Congo or its nine neighbours to demonstrate that the financial proceeds have not contributed to fighting.

Congo and Rwanda had been working closely on the issue before allegations of Rwandan complicity in the M23 rebellion brought about a breakdown in relations.

Rwanda has historically benefited from the exploitation of hundreds of millions of dollars of Congolese minerals.

A U.N. report in December last year said that Bosco Ntaganda, one of the leaders of the current M23 rebellion who is also wanted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes, was continuing to smuggle minerals through Rwanda.

On Tuesday the advocacy group Global Witness said that its research indicated Rwanda was continuing to launder proceeds from minerals that may have benefited armed groups.

“Not only does Rwanda’s predatory behaviour jeopardise its own reputation, … it also risks undermining the credibility of initiatives being developed to tackle the conflict minerals trade,” Global Witness spokeswoman Annie Dunnebacke said.

Last year Rwanda returned to Congo more than 80 tonnes of smuggled minerals that had been seized by customs officials.

Source: Reuters.

September 18, 2012 No Comments

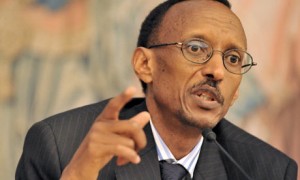

Q&A: Rwandan President Paul Kagame answers TIME’s questions

By�ALEX PERRY�|�September 14, 2012.

In the midst of a crisis over an army rebellion in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which the United Nations has accused Rwanda of supporting, Rwandan President Paul Kagame allowed TIME unprecedented access into his working and daily life. Africa bureau chief Alex Perry interviewed Kagame four times over five days, at his office in Kigali, at home with his family and at a regional summit on the DRC in Kampala, for a total of seven hours. Excerpts:

TIME: I�m not here to portray you as a saint but I wonder how you assess the recent press coverage, calling you a despot and a dictator?

Kagame: I don�t want to be a saint. I don�t even attempt to be. It wouldn�t make any sense. It would divert me from my responsibilities. Concentrating on being a saint would end with me doing nothing that I was supposed to.

But reading the newspapers, watching the television, it has been really ridiculous. It has no sense of justice, fairness or logic. They are talking about the situation in Congo. But they are never talking about Congo; they are talking about Rwanda. Which betrays everything about their intention: not to pay attention to the problems of Congo, not to solve these problems, but to abuse and kick Rwanda. We have the U.N. now engaged for 10 years. They have thousands of soldiers in the DRC [Democratic Republic of Congo]. The whole mission consumes $1.2 billion a year. But where are we after 10 years? How have you made not even a dent in Congo�s problems? The origin of the problem is linked to Rwanda � the FDLR [Democratic Liberation Forces for Rwanda] and genocidaires who live in the Congo and have been there now for 18 years. Have we come anywhere close to resolving that problem? Or should we just sit back and say that just by the mere presence of the international community and the UN, everything has been addressed?

These are enlightened people, people who always tell the world how well intentioned they are and how they want to see global security and fairness and justice and who are respected by all. And they are the ones who are turning everything upside down. This is the law of the jungle.

But bad as it is and shocking as it is, it is not surprising. It�s the same world we know, that we have come to try to understand how we might live in it, despite all the injustice and unfairness. It�s like living in a hurricane zone. The hurricane hits Rwanda and we take cover and hold our breath � and then it passes and we pick up the pieces and move on. We keep moving forward. We keep building our own lives.

TIME: What�s your response to the allegations of support to the M23?

Kagame: In March, after elections in Congo, we were being accused of being too close to Kabila. All of sudden it changed and we were No. 1 enemies. There was talk and press about how we must arrest CNDP [National Congress for the Defense of the People leader] Bosco Ntaganda. �He is dangerous. He has violated human rights to the highest level. He is a criminal.�

We said: �Wait a minute. If you are interested in this man, we do not mind or care, go and arrest him. You have forces in Congo. What does it have to do with us? Since we have Nkunda [Laurent Nkunda, former CNDP leader, detained by Rwanda in 2009 after Rwandan troops, with Congolese permission, intervened in eastern Congo to stop an earlier CNDP rebellion], we must also take this guy? Rwanda becomes a prison for fellows they throw out of Congo? Are you really saying that these people are not really Congolese but Rwandan?�

I actually called President Kabila on April 4 or 5.

I said: �We are getting a lot of people coming to us talking about the arrest of Bosco Ntaganda. Are you involved? You should be the one asking us?�

He tells me a story, how these people have also been coming to him. �I am not going to give Bosco Ntaganda to the ICC,� he says. �But Bosco Ntaganda is indisciplined and I want to arrest him.�

I said: �But why all this international outcry and pressure? Why don�t you send some officials that you trust and deal with the matter so that we don�t lose trust in what we are doing together.� Because we had already started discreetly deploying our forces. These forces were working with his people to hunt down the FDLR. We didn�t want to lose track of that.

So he sends people there. They asked if we can call the leadership of the M23 and our people accepted and they met just across the border in Rubenyi. And they [the M23] spelled out their problems. �They do not pay salaries. And we are hearing that the government and the international community wants to arrest Bosco Ntaganda. Ntaganda has flaws, but we think if they get Ntaganda, they will come for another, then another, then another. Some of our fighters have already disappeared. Is this all another way of eliminating us?� And the Congolese said: �Most of these things we are aware of and they are legitimate and we are sure the President will address it.�

Our people at that meeting kept insisting: �Address these legitimate issues. You need to avoid anything that will escalate these problems to a level where you have to turn against each other and start fighting because it is going to take us back maybe 10 years.� Because had good information that the CNDP was preparing to resist.

The next day President Kabila comes to Goma with money for the soldiers: $10 to this one, $5 to this one, $1 to this one. He says: �Now I have resolved the issues of salaries, I want Bosco put aside from the army. Understand that these issues have been resolved.� That�s when the fighting started. And I talked to Kabila again. He said: �We are seeing these things escalating.� And I said: �But President, you are the one escalating it.�

And all of a sudden an accusation comes up Rwanda is now supporting this M23, giving them weapons, uniforms. A number of them speaking English. They must be Rwandan. These stupid, wild things. And the whole world believes it. It goes to the Security Council. And the [U.N.] Group of Experts comes up with this whole thing� I�ve never seen such a stupid story like that. I do not think it�s because people are stupid. But I do think they want anything that implicates Rwanda, whether it is wrong or right. The M23 is [made up of] deserters. They go with their weapons, right? [Plus] the government soldiers were just running away and leaving weapons. The deserters were picking up what they wanted.

And the whole thing starts spinning out of control. We are trying to explain: �Look this is how this started, these are the facts.� But nobody is listening. They wanted Rwanda always to be seen as the culprit in the problems of Congo. Congo is a victim, always. The President, the government, everybody is a victim of Rwanda and Rwanda is the culprit. It doesn�t need a rational story, it doesn�t need facts or logic. It�s just how they want it.

TIME: Do you think that�s it?

Kagame: I can�t find any other explanation.

TIME: I read it like this. You come out of the genocide, which the world did not help you with. Then the genocidaires go to Congo, and the world feeds them. Then you have chaos in Congo for 18 years, the world puts its biggest ever peacekeeping force in � and it doesn�t work. And that builds in you a very robust self-determination. The flip side of that is that you question the world system [of international intervention] and the effectiveness of, say, the U.N. and the prerogative that an organization like Human Rights Watch assumes when it pronounces on human rights in Rwanda. You question what these people do for a living. You�re questioning their existence. Or you�re certainly questioning their right to define the narrative on Rwanda. And so it becomes a very personal fight.

Kagame: That is a very big part of it. Is this what the international system has been reduced to? Another question is: What�s wrong with self-determination? I understand some of these [aid] groups on the ground try to create an environment where they become indispensable. But how about countries? How do they not see?

TIME: Most NGOs absolutely concur with the right to self-determination. They talk about it all the time. In theory, you and they agree. What happens is that that kind of discussion is naturally quite heated, quite emotional.

Kagame: Yes it�s emotional, it becomes personal. But I just don�t understand how the rest of the world also gets deceived. And I want to say: we are not going to abandon these years of self-determination or self-respect, of survival and living for our people and our country just because there are people who are getting personal. It will come and go. It won�t stop our way of life. If anybody is questioning our determination to stay the course� This is about overcoming our past, having a decent living for our people. It�s an issue of our rights. [After all] what�s the alternative? People who have given up and surrendered and accept being treated the way they are treated � the way people want to treat us � what have they gained from it? We are better off.

TIME: A lot of people ask: �Why react like that?� After all, Human Right Watch does reports on every government in the world and plenty ignore it.

Kagame: These powerful countries can ignore it and get away with it. Nobody threatens them. But for us it is a different situation. They are building on our weak position as Rwanda or as Africa. The issue of aid comes in. We need to explain ourselves, otherwise we end up in very had shape. I�m not saying that if asomebody is doing something wrong, they should not write about it. But if you are seen to be selective and pursue an objective rather than deal with human rights violations, then it will shatter your credibility. People will think you�re not serious. This woman at the U.N. Human Rights Commission in Geneva, [Navi] Pillay, says: �These M23 are dangerous people. These leaders, they recruit children�� But the FARDC [Congolese army] kill children. They are among the worst abusers. But everyone keeps quiet about it. [And what about these] people [the M23] with legitimate grievances who stand up to their own murderous government, a government which is killing their own people. This is an imbalance in the system.

TIME: I know you realize that if you didn�t react, there would less headlines. But you�re making a point here, right?

Kagame: It is a question of principle. If you keep writing about me in the papers that this is a violator of human rights, and the story of my country and my people is totally different�and it is repeated by people � then it is a question of the right of response.

But it�s not just about principle. This narrative ends up at the UN, even with action taken on it. It turns into a fact and some kind of actionable thing. This has consequences. And I should keep quiet? No. It doesn�t make sense.

TIME: I have a theory: the institutions and structures of world opinion and the international community are set up for an Africa of disaster, of famine, of wars. It�s about peacekeeping, it�s about saving babies, it�s about pointing out where governments are failing. And I wonder whether those structures are poorly adjusted to dealing with a country that demands respect and sovereignty and the choice to tell its own story?

Kagame: You are really putting it in the right way. This is the matter. Look at aid. We agree that it is about helping people to stand on their own. But at the same time [it works out that] they actually they fail to stand on their own. They are dependent.

So you have two tracks. [The international community] talk about self-determination. Human Rights Watch says we are all on the same page. But at the same time it is very clear that you are also creating a situation that undermines all of that. That is what Rwanda is facing. Should Rwanda accept it and say this is the way the international community works and we remain where we are? We say: �No. We have a respect for the international system. But we also have our own self-respect.

Time has already shown the results. You know this place. You know where we have come from. We are making good progress. Even the poorest of the poor will tell you we are in a different place than we were yesterday. From $1 a day we are now $3 or 4 or 5 or 6. And this has happened under this kind of pressure, this jostling between self-determination versus the international system, which says: �There are some people who should stay where they are and we are the only ones who can determine how and why they get out of this.� It�s a struggle every day.

TIME: Are you more able to confront the West as the world becomes less unipolar?

Kagame: Oh yes, absolutely. This old way of doing things is weakening. There are more countries, more people, who are seeing it the way we describe it. And even getting more angry about it and wanting really to challenge. What we are doing, we are not doing it alone. It�s a common thing that�s spreading, particularly among the ordinary people of Africa, civil society and business leaders. They think we are being treated unfairly, we are getting a raw deal, we need to be better than this, we need to be seen to be better and more capable.

I also think we are seeing more centers of strength, political, economic or otherwise. It�s not longer just unipolar, with one part of the world having everything and deciding everything for others. The ground is really being fairly and speedily leveled through innovation, entrepreneurship, technology � all these things are falling in the hands of many, globally. It�s no longer a monopoly of one part of the world.

TIME: One thing that accompanies that diversifying of power is the emergence of the idea that there are different ways to progress. Singapore or China or Turkey follow a different political system to classic Western democracy. Does that apply to you as well?

Kagame: Always it�s a matter of time and process, and an issue of where you start from. In our case, we started from a very low base on everything. We have got to take everything forward and we prefer doing that all together. We haven�t chosen socioeconomic transformation at the expense of democratic governance. We need to make progress on everything at the same time. People imagine that we emphasize one at the expense of the other. But it�s not true. In our case, most of the successes we have had in socioeconomic transformation would not have happened if it was not integrated with the democratic governance that built on people�s right and freedoms. Socioeconomic transformation cannot happen by coercing people to do it. People here tell you how much they are part of the development taking place, how much they are part and parcel of the decision-making, how much they have benefitted. I see no better way of achieving what we have achieved.

When there are reports from outside, there are two messages. That there is significant, good progress, on all fronts. Others see socioeconomic progress at the expense of freedoms. But where are the lack of freedoms? The Western model, whatever it is, I think they are talking about people. If we are doing what people are happy with and are part of, how can what is happening here be without freedom?

TIME: You do draw a line, on political freedom with people who might want to start another genocide, though.

Kagame: In any country, even if it is an advanced democracy, everything is contextual. What was happening in America 100 years is not what is happening there now. If you look at America today, some people have become disillusioned and skeptical. They say: �Phurr� politics! These leaders of ours.� They talk about �Washington.� Even the leaders from Washington are bashing Washington. Sometimes they don�t even want to cast their ballot.

In 2003 or 2010, [in our elections], our turnout was 96-97%. Why? The West says: �These fellows must be on the backs of people.� But can you imagine somebody in hospital begging and saying: �Please bring the ballot box here because I want to vote?� Somebody going to the polling station holding their IV drip because he has the urge to vote? By midday it was all done, 100%. How do you equate that with �Phurr� Go to vote? Why?� You cannot expect things to happen in the same way there as they happen here. It does not make sense, it has no logic. There are different stages. However, there are principles. If you are able to say that you are answering to the wishes of the people, is it the best thing for them at this time, then you have reason to believe: �Yes. This is how it should happen.�

TIME: What do you make of the aid cuts that have come in the wake of the Congo controversy?

Kagame: It�s mainly symbolic. And it�s not cuts, it�s suspension. People excitedly are writing all kinds of things and betraying their attitudes and wishes. They are celebrating, thinking Rwanda is now dead. �This should have happened long ago.� But the story I want to talk about is slightly different. How has all this happened?

It has happened on account of the Group of Experts� report. But look at it. The Group of Experts wrote a report that is entirely one-sided. Most of it is the government of Congo, military leaders, government officials and different groups. They wrote a report condemning Rwanda and making Rwanda responsible for everything that went wrong there. The UN hurriedly put it out and Rwanda was crucified. The donors jumped on it. They pronounced the suspending [of aid] � really wanting to punish Rwanda for it.

At the end of it, when things cool down, we say: �Aren�t you being unfair? You hear from one side and then you shift the blame on the other side you have not even bothered to hear from. Is it right? If you really wanted to condemn Rwanda, at least try to disguise it. At least you must be seen to have been fair, trying to ask both sides. Why don�t you give us a hearing? You have already judged us and condemned us.� And they send their experts here but at a time when we have already been condemned and sentenced. What on earth is this? Why do you want to hear from me now, when everything that would have happened has actually happened? The full report is likely to come out in November. But I don�t see this Group of Experts changing what they wrote about us just because they heard from us. I think that what they are likely to do is to maintain that they were right. Because they cannot be seen to have made a mistake. The whole thing is just cosmetic. The whole international system is awash with so many blunders and errors.

This so-called free world of ours� When you see how these facts being ignored �we wonder which free world we live in. You, you want to dig out facts. But probably you might be the only one in a thousand.

TIME: The great joy and sad truth about covering Africa is that getting a scoop is really easy � because nobody�s out there. You�re actually catching Western journalism at quite a weak moment. There are cuts. There are not many people around. Most the stories you�re talking about are done from London or New York, without a single Rwandan quoted or any mention of the genocide.

Kagame: These people were coming to us, telling us we had to stop Bosco Ntaganda, posing as people who have values and want to defend human rights. And I ask: �Do you ever feel guilty or foolish that you come to me to talk about this recent problem of Ntaganda and keep quiet about these murderers of our own people in that same situation? These people are living there, raping there, killing Congolese people every day, killing children. You keep quiet. You have forgotten all about that. And you come to me, telling me to help?� This is just an insult, you know?

In Congo, if you look at the government, the President, his ministers, on the radio urging Congolese to kill these Tutsis. To some people it�s normal. Even to these people who are telling us about human rights. It�s normal because it�s Congolese and it�s normal because it�s against these Tutsis. In the end, those who say they are on the side of the victims have turned into perpetrators. It�s pathetic.

From our side of things, there are things we want to live for and are ready to die for. There are things we cannot deviate from. The issue of our rights. We have sunk to the lowest level, we can�t go lower. You cannot threaten us. There is no threat anywhere that can change our minds about how we should be and how we should fight for our rights. People can threaten this or that but we have had worse things. We will do what we feel and what we believe. We cannot be diverted. We have not offended anybody. We haven�t fought anybody�s interests or rights. It�s just about how we survive, how we live on. And nobody is going to do it for us. Nobody is going to do it for us.

[INTERVIEW RESUMES AT KAGAME�S HOME]

TIME: We were talking yesterday about the storm of accusations that Rwanda has faced�

Kagame: Is this how you are going to run the world?

TIME: � and you have a summit on Tuesday and Wednesday in Kampala at which African leaders, the Great Lakes� leaders, are going to discuss an African force to intervene in Congo and try to achieve peace where the U.N. has failed. Do you think you can succeed in Kampala?

Kagame: I am trying to figure out, with all this noise, where are we now? Is Congo any better off? Is anybody better off? Are we in a better situation than yesterday? All this misrepresentation� Are we any closer to dealing with the problem, any closer to a solution? Maybe we are actually worse off. Not Congo, not us, not the donors, not the internationals who make so much noise. I do not see anybody who benefits from this. Nobody.

And the problem of Rwanda, which for many years has been one of security, these murderers who live in Congo, this problem never features. We should not just be used to find solutions for other people�s problems when ours has been forgotten. So I am really taking a back seat in this. Rwanda is not going to be unhelpful. But we are not going to be forced to take the lead. If anybody though that accusations which falsely blackmail us was going to make us more useful, they got it wrong.

The idea of a regional force came up in Addis Ababa [at a previous International Conference on the Great Lakes Region in July] but then it�s a regional force to do what? Congo thinks it�s meant to help those opposed to them. Congo thinks the world owes them a solution, that someone will just come and provide a solution. They think it�s meant to monitor allegations of Rwandan support to the M23. And while that has never been the case, one would want to know why such a force would not be also monitoring support by the government for these genocidaires.

But in the end, this is just diversionary. A solution at the end of the day is political, not military. If the government of Congo is not going to do things to bring about a solution, and bring about some understanding, to what are very serious and legitimate grievances� I do not think you can shoot your way to a solution. They�ve tried it and it hasn�t worked. You have a whole army of tens of thousands collapsing because of a few hundred rebels. That tells the story.

My relationship with President Kabila has been gradually eroded by things that have happened in the last few weeks. Kabila is used to playing games and the international community entertains that and plays games with him. They tell you one thing and mean something else. We have been talking and trying to find a solution. At the same time, he was sending emissaries all over the world to abuse us. He says we can be part of the solution and at the same time he is making very serious allegations against us. The relationship has been affected.

TIME: How has the recent storm of controversy around you affected your family?

Kagame: We try to keep them out of it as much as we can. They don�t need to be part of it. They�re better off leaving the burden to us.

TIME: You�re a very close family.

Kagame: Sure. That�s what we want. We like it. It works very well for us. We are closer than even you have been able to see.

TIME: You met Jeanette in 1988. Is it her, and your family, from which you draw so much of your sense of purpose?

Kagame: I really find a lot of strength [from them]. My moments with my wife and my children have the highest value of any moment for me. I take some relaxation from it. It takes away any bad days I have had. It�s very refreshing. I can start all over again. It�s been that way right from the time we built our family, and it gets better every day. We go out together in town to restaurants, to meet friends. I try as much as possible to give them a normal life.

TIME: Are you working 24/7?

Kagame: It comes close to that. Either working or thinking. [But] it turns out to be some kind of fun, also. It�s like you cannot do otherwise so you try to enjoy it, try to find some life in dealing with complex issues. It just becomes a way of life. People look to you got a way out of this mess. And you enjoy that responsibility in the end. At certain times you do.

That�s what I am required by Rwandans to do for them. The good thing is Rwandans are very, very responsive to the needs of a situation. They play their part, I play mine and that�s how we manage to make good progress even under such pressure. In the outside world, a number of times I have met people who say: �The whole world has descended on Rwanda! The country is being torn apart!� And they find people here are still in one piece and they get surprised.

TIME: There are few greater contrasts in the world than crossing the border from Rwanda into Congo. In one, street lighting, smooth roads, law and order, development; walk a few feet and it�s unpaved and potholed, there�s rebels waving AK-47s around, there�s refugees, there�s no power and terrible poverty.

Kagame: And that contrast is taken is a negative. We are held responsible for this difference. No. Compare us with ourselves. Look at our history and see where we are now. That�s a better comparison than comparing us with Congo. The two are different and have different histories. For us, we are doing it for ourselves, not as compared with Congo or anybody else.

It should be the same in Congo. If you look at the size of wealth of Congo, the question is why should it be like that? Why does Congo look like that? It shouldn�t. [Comparing us] becomes the false basis for making a judgment against us. Some people try to explain the difference by saying Rwanda must be exploiting the wealth of Congo. Do they think that�s what lights our streets and puts up all these buildings in our city and builds our roads? That�s a very shallow way of thinking.

Maybe people who raise these issues should be asking themselves a simple question: why does Congo, that has this wealth, not thrive on it?

TIME: Very few critiques of Rwanda�s actions in Congo fail to claim that Rwanda has large business interest in the east, including farms and mines. Is that true?

Kagame: I do not know and I really do not care. What right do other companies from China, America and wherever have to be in Congo that companies from Rwanda do not have? There are companies there from all over the world. We are probably the first country in the world to be accused of being guilty of having an economic interest somewhere. That�s common practice. How can we be guilty of that?

The relationship between Congo and Rwanda has been there since time immemorial. Why has it suddenly become strange? There is a lot that goes on between us. It�s not about trade or smuggling. It�s a blood relationship. To say this is all about Rwanda�s business interests is very simplistic. People who go to do business in Congo do not have to ask me, just as people who come from Congo do not have to ask me. They are saying Bosco Ntaganda has a house in Kigali. So what? I don�t know anything about that. But I do know that there are ministers in Kabila�s government who also have houses here. Congolese investment here because it is safe here. We have a lot of foreigners coming here and building houses. Maybe, if you looked carefully, you would find that Kabila himself has a house here. I don�t know. But I would not be bothered. We do not differentiate when it comes to money unless it is money that you killed people for or money that is questionable. But if you invest here, what�s the problem?

Who�s making such accusations? The same people. They say: �That�s how Rwanda earns a living. By being in Congo.� And all along this � mobilizing support for their side, raising money for their campaign � it�s actually an economic interest for them. It�s actually how they make a living. So I don�t even understand the meaning of the accusation.

You see, independence for us is in a very broad, including economic independence. The RPF has companies involved in businesses. It�s not something that started yesterday. It�s something that originated with the beginning of the struggle. We mobilized people, they made contributions towards the struggle, people would give us much as they had or could afford. We said: �We cannot just keep drawing money without making sure we do something to actually multiply this money, making it more dependable and sustainable.� In fact, when we took over in 1994, we ran the government here with money collected by the RPF. There was literally nothing here. That�s how we started created economic activities for the country and our companies improved themselves and made business. Many people have talked so much about the source of our wealth but for us it has that meaning. It may not make sense to some people but it makes a lot of sense to us. We have no apologies for it at all. We only have to make sure there is no mix-up [between] what belongs to the RPF and what belongs to the state, to avoid any conflict of interest. And all along what we did was for them to invest in certain areas where other people were shy to put their money so that we achieve another objective: to really stimulate and start another activity which should benefit the country

And if Rwanda�s interest really is economic, as people say, why not call Rwanda�s bluff? Deal with the security problem. Then Rwanda would have nothing to hide behind. Our problem in Congo for 18 years has been a security problem. You are saying we�re interested because of economics. Deal with the security so that it does not exist and then we can all see what crimes we are committing in our economic interests.

These are things that play into how the international system is built. It�s anything goes. It�s no longer justice, it�s no longer fair or has any level of honesty. It�s just the law of the jungle. I am not trying to say that things are clearly black or white, that the developed world is wrong and that the developing world is right. It doesn�t happen that way. Even with the grievances with how the situation is mismanaged and misdirected, even with all these people to blame, whether in human rights groups or governments or as individuals, I still think there are those who are really doing their best, who are adjusting very well to this new dynamic of wanting to see things differently. People are shifting and looking at things differently.

But there are others out there � bureaucrats � who do not want to step away from the old ways of thinking. It�s that attitude of looking at Africa as people who must get in shape and who must be punished when they try to deviate from what has been established as right. We still have many people who think like this. They are continuing with their way of being influential in terms of decision makers and making decisions. They put pressure on the Prime Ministers or secretaries of development to act against Rwanda, and in some cases it becomes effective.

We should not accept to be treated like this. And the best way to resist is not just saying �No� but also to be doing what is right. That will defend you more than just making claims of sovereignty. We must govern and lead our people and do what is right. We have to put our house in order in order to claim our rightful place. We cannot just claim the place. We have to earn it. We do not expect anybody to hand anything to us, At least, I don�t. And then, over and above that, assert ourselves. If we do not fight corruption and govern well, we have no ground to stand and say: �Do not treat me like this.�

That�s why in Rwanda we can comfortably resist. Our people are with us. When you attack one, you attack us all. The rest of the world tries to create discord. They try to make claims and bring divisions among us along the lines of ethnicity. But they have failed. They do not know how far we have gone in our history. They try to bring the country to its knees but they have not succeeded. When people mistreat us, there has not been much success.

I take consolation from that. What you see happening in Rwanda, it�s part of our struggle and our ideology. Everyone in Rwanda shares the view of how we should lead our lives. With self-respect, and respecting others as well, and knowing that nothing comes easily. We fight these battles together. We are really together in this. I have played a part in this but it has developed its own dynamic, a life of its own � it can continue without me.

And with all these challenges, these injustices, I have found they tend to strengthen us rather than weaken us. Out there people are even angrier. People are saying: �What does the world want with us? Why don�t they leave us alone to live our lives?� So I think we are left stronger.

TIME: How significant are the aid cuts?

Kagame: There has been much excitement in the media. But it�s suspension of nothing, really. The Americans suspended $200,000. And the media blows it up and says: �America has turned against Rwanda.� There is jubilation. They wanted to give the world the impression. �We have got Rwanda where we wanted it.� But it�s not true. It�s $200,000 for one year. This is really silly. In fact, this is money that they owe us because for two sequential years they did not pay us. It�s really ridiculous.

TIME: When do you think Rwanda will be able to leave behind aid and move towards, as you see it, true independence?

Kagame: I can�t put a clear date on it. But looking at where we have come from, in another 10 years we should be close to that. We won�t have achieved it but I think we will be very close. As I said, we are stronger every day.

TIME: And that�s a core objective for you?

Kagame: Yes, it is. It not only makes people more independent, it actually puts them in a position where they are stronger in their beliefs, committed to them, and more advanced in things they demand of us. More democratic governance � it will be more entrenched. Prosperity will be more visible. People�s ability to really determine their destiny will become clearer. It�s very important. It�s not the life anybody deserves to live, a life that is controlled by somebody else or somewhere else.

TIME: Your experience of the struggle, you say, makes you stronger. But such an unprecedented struggle, it must have broken some people.

Kagame: Not so significantly. What I see is actually more determination. You go through rural areas and people say: �What is this I am hearing on the radio? What do these people want with us? Why don�t they leave us alone?� It has this effect. I do not think it�s just me feeling like this. Even if it was, I try as much as possible to transmit it. And I have found a good reception.

If you look at Rwandan blogs, when these aid cuts were announced, they set up a fund to replace the aid. They use SMS to collect the money. We are perhaps running into a few million already. This is just self-generated by Rwandans across the world. It shows you, even if it does not promise much money, the idea is something interesting.

[INTERVIEW RESUMES AT KAGAME�S OFFICE]

TIME: One of your innovations is to combine politics and military, to have a politicized army.

Kagame: We really tried to make the dividing line as thin as possible. In our struggle which, in a way mirrors some other struggles � like the one Fred [Rwigema] and I were involved in in Uganda; and also Ethiopia and Eritrea � it combines these two very well. It grows militarily from the masses, from ordinary civilians who from the beginning are part of the struggle. We always try to maintain this. This fighting capability we developed, we shared the lifeblood [with civilians]. One feeds the other.

Again, it�s really part of this whole philosophy of self-determination, being independent, making sure that the whole essence of the struggle is to make people more free, make them feel they participate in the decision-making, they share problems, they share solutions, they share the benefits together, all the time together. Happily it seems to have worked for us.

TIME: Can you see why people might say: �Here�s a political party that has a definite military edge. Here�s a political party with big interests in the economy. This looks like Stalinism.� You�re saying there is a different, pragmatic explanation for this and people have never understood that.

Kagame: They have never understood. Much as we have tried to explain. That�s why sometimes the understanding of these things conflicts. And some of those who criticize, you find they do the same things in the West. I was asking how they raise money for their campaigns. Well, you find they have godfathers in business. Why wouldn�t any say: �But these parties are indebted to these individuals? Don�t they behind the scenes have to pay back? Is this any better?�

It all starts with people who think we have no right to be seen to be doing the right thing ourselves. It is like the world has decided to divide itself into two: the parts of the world that whatever they are doing is what is right and must set the pace for the rest of the world; and the rest of the world, which can only be doing the right thing if they are told what to do it by the other. But then this contradiction comes in. When you do similar things to others, for some reason they say: �No, no, no, you can�t be doing that.� It�s as if it�s only for them.

TIME: You�re saying you came up with something new. You worked out what you thought was the best system for the country and the best way to achieve it � and it didn�t fit anything that came before. In fact, it deliberately drew on Rwandan culture and was specific to this place � and people who come here and try to spot another system are going to misunderstand it.

Kagame: Absolutely. We are sticking to what works for us. Sometimes we get caught up in some double-standards and hypocrisy. Some people will just criticize, even if what they are criticizing mirrors something they are doing themselves. They don�t want you to do it. They say it is not for you. Or they think it is not for you to be able to do it unless you have first had clearance from them. We have been very, very careful, building on our cultures and traditions, and also modernizing them.

We are also very, very conscious of the fact that we are not an island, and very conscious of these universal values and feelings.

But the fact that we are firm on insisting on what we are convinced is right for us causes a lot of discomfort for many. There are people who don�t expect us to argue, to present our case, to even try to convince. �We don�t expect this from you.� It�s like: �We expect this and when we tell you this, that�s what you must be doing without any question.� But if you are really talking about freedoms and values to uphold, then why don�t you listen to my viewpoint as well, why don�t you allow me to also express myself, why do you want to cut me short, why do you want to silence me?

TIME: Human Rights Watch characterizes you as a regime that�s intolerant of dissent. You are saying they are intolerant of your freedom to have an opinion.

Kagame: Absolutely. If you want to make me keep quiet, if you want to silence me and you want me to swallow what you are telling me and not listen, then you are exactly committing the same offense you are accusing me of. They say: �Rwanda continues to deny this and this. They should accept it.� We should accept it because they are the ones saying it. In the end, they really indict themselves.

TIME: Can we go very specifically into the situation in Congo and the M23? How would you characterize your relationship with actors on the ground?

Kagame: Our story starts with 1990 when our struggle started, and then in 1994, when we had the genocide and refugees running to Congo. So that period, when Mobutu came in and helped [the genocidaires], from that time Rwanda found itself swallowed into this big mess of Congo. And then you have the history of the international community and how they messed up and meddled and did all kinds of things. They were feeding genocidaires, giving them help and food in camps that were militarized. They were calling them refugee camps and you would find anti-aircraft guns and APCs and all kinds of weaponry in the refugee camps. And the world wants to tell you these are refugees.

This is not something that people need to analyze or think hard about. But they try to convince people otherwise or even ignore. One failure was adding to another. This constant here for us, which always dragged us into this, was relating to this genocide history and the threat that is always there, one way or another, from these genocidaires. Whatever we have done, has been this. Either working with the government to try to deal with this, trying to deal with it ourselves when nobody is listening, the international community coming in and blaming Rwanda for everything � the whole history of Congo.

But of course there is this other angle. There are these Congolese of Rwandese origin. The way it plays out is very complex. I think even under Mobutu they have always been seen as kind of secondary citizens in that country. It�s like they really belong to Rwanda, they don�t belong there. So to an extent, the problem is attributed to us.

And really this messy international system has been part of it. You know, we gather a lot of intelligence on the ground in Congo. And until recently some of these people � in the media, the NGOs � were discussing among themselves and they were saying: �We really want to fix Rwanda. But we have failed. We have been failed by Congo. We are helping people who are incapable. We tried to fix Rwanda and do it for the benefit of Congo, but these Congolese they are useless, they run away, they can�t fight.� Now they are trying to fight it and have another day with us again. It�s no longer the suffering of the people in Congo. It�s just this mess.

We try to manage it by drawing certain lines. Things happen the way they happen but there is a bottom line. There things for our own security, our own existence, we will not have. [In the late 1990s] when certain red lines were crossed, we had to take the bull by its horns, and in a very costly way, in a very, very costly way, with the whole world descending on us. We did what we needed to do and short of doing that, we would not be there today.

TIME: Because the allegations are so persistent, I do need you to state for me in your own words exactly what Rwanda�s actions are in Congo.

Kagame: This situation we are dealing with, we never thought we would have to come back it. We had created a good relationship with the Kinshasa government and, to an extent, succeeded. To a point that they had accepted our forces to go into Congo and work with their forces to eliminate this threat for us that has always been there. That the U.N. and others have forgotten all about, though their presence their today is premised on that.

So this was a very good relationship. This is why we�re really upset, to the point of being seriously offended. Things changed in a matter of days, maybe weeks, but really a very short time. All of a sudden some kind of wedge is being driven between the two countries. [What was a] security problem has grown in other dimensions. It is now political, diplomatic, it keeps feeding into these human rights groups, then the media.

We are trying to stay the course and say: �For us the problem has always been that nobody is going to come and sort out this problem. We only have to sort it out ourselves, and especially by working with the Congolese.� Because we have gone back to almost where we started from. These [genocidaire] groups are now part and parcel of government forces. Yesterday we were hunting them down together, now they are back to the Congolese side. It�s so confusing, it keeps changing. But for us, we stay the course and say: �Our problem is this.� We will work with the government to eliminate this problem. If something good happens for Congo, in the end we also benefit because Congo becomes more responsive to our problems and we work together and so on. But it takes two to tango. You may have the best intentions, you may have certain capacities to deal with issues but if there are issues you share with others people, it is just a 50-50 thing. There is no way you can do 100%.

Take this man, General Nkunda. We took on the burden. And you know, when we held him here, normally human rights groups would be very hard at us. �You are violating somebody�s rights, you are holding him.� But they are quiet. Actually, they are happy. So they are sectarian themselves, in a sense.

[But our actions] can contribute to a bigger problem. By doing what we did, we allowed some sense of stability in eastern Congo and for government to build on from there � which they didn�t do, unfortunately. And they thought this was the way to solve their problems. Before we are done with this case [Nkunda], they want to bring another one [Ntaganda]. And maybe a third. It goes on like this. In the end, we turn out to be a prison for these Congolese which are not wanted by their own government. Why these so-called human rights groups don�t see that as a problem? It just indicts them.

TIME: And your relationship with the M23 is what? You�re an interested party? You speak to everybody?

Kagame: Actually it is more in the minds of others. There is nothing like a relationship between us. It is in the minds of the Congolese and the minds of those associating with the Congolese against us. You see, some of these Congolese of Rwandese origin� There are blood relations. People having uncles, aunties. There is no way of policing it. I hear these stories of Afghanistan and Pakistan � it is blood relationships.

When we talk to Kinshasa government, we say: �You seem to be bent on wanting to resolve this militarily when this is actually a political problem.� But in their minds, they were hell-bent on just saying, no, this is a military issue. They had units that had been trained by Belgians, South Africans � they really wanted to overrun. But they forgot: these are their own citizens, their own army. So when they insisted on wanting to solve it militarily, they failed miserably�

If we had not come to their [the Congolese] rescue, they [the CNDP] would have defeated them in 2009. In fact, you probably remember, they almost overran Goma. We thought, and the whole world thought, this is going to be catastrophic, with refugees and all kinds of people dying. [At that time] we really sent a very strong message to them. We said: �Look, we really have been trying to keep out of all this. But if you keep continuing to advance to Goma, we are going to step in on the side of government. And work with them to stop you. And actually fight you. Probably you don�t want us on the wrong side.� And that stopped it.

This time, we stated right from the beginning: �We don�t have to come to that point. This is now a political issue that you need to solve politically.� So when the government was defeated � and defeated by their own soldiers � they started saying: �Oh, these people, Rwanda�� They were trying to find an explanation for this defeat. The whole army crumbling from within. They were saying: �No, we couldn�t have crumbled like this.� They told the world it happened because a hidden hand came in with muscle and created this problem.�

How do you then say that it�s taking a superior force to defeat an enemy that is actually not fighting? It doesn�t take any force at all. The army is just not fighting. It is just running away. You cannot even say they have been defeated because they didn�t even try. People say: �Rwanda is supplying arms.� No. We are not that generous to start supplying arms where they are not needed.

For this reason, we start calibrating our involvement. And pulling back. If anybody thought that by telling lies about us and trying to fix us, it was going to be an incentive for us to help, they got it terribly wrong. We will avoid doing the wrong thing in terms of taking sides in this conflict. There is no way anybody can force us, by saying: �You must help.� We focus more on our problems. And if anybody crosses our border, they will find that we are not very kind.

TIME: Let me pick up on that, in a different context. You�re firm. Opposition groups, exiles make allegations that there are assassination teams wandering around trying to kill them, that when it comes to opposition, whether it�s expressed in journalism or politics, that Rwanda is a narrow space.

Kagame: We have a very narrow space for people who feel they are not accountable. If there anybody who thinks they are above the law, who thinks they are not accountable to the systems and the laws of this country, and if somebody thinks they can use any means for their political ends, they discover very quickly that this is not going to work. Some of things that happened here will never happen again.

Now, unfortunately, while I�m putting it this way, people build on it and say: �He is saying something else. It�s political space.� But let me say this. If you look at all these people who are outside � all of them who are active, whether it is in South Africa, a couple in the US, and the others � there is not a single one who does not have a serious case, a charge here in Rwanda. In some cases, not even political, outright criminal. If we are going to have people out there claiming persecution of some kind but actually it is somebody running away from a case of, say, corruption, how does that become lack of political space? Nobody here who tried to have a different political view was punished for that.

This one in South Africa, [dissident General] Kayumba [Nyamwasa, former Rwandan army chief of staff, now living in self-imposed exile in South Africa, where two attempts have been made on his life] is saying in the press in South Africa, actually I was trying to make a coupe happen. If you have somebody out there saying �I wanted to carry out a coup,� and later on he is shot, maybe he deserves it. Because a coup means he wanted to kill people here. You are really indicting yourself by saying �I wanted to kill people in order to make a change happen.� It�s like you are really declaring war on a country.

Or take the former prosecutor-general [Gerald Gahima] who is in the United States. This fellow was involved in a gross case of corruption. He was a prosecutor general. He was in charge of an investigation of a bank that has serious issues and took money from the very bank he was investigating. The facts are there and in the end when he was found to have done that � and by his own admission, he used his mother�s name and stole millions � he did not even deny that� When this came out very clearly and he had just been appointed vice-president of the Supreme Court, we actually were obliged to fire him. He stayed a few days here and then escaped. And when he reached there, he says: �Oh, politics, RPF!� It has nothing to do with lack of political space. It is lack of space for space for people to do corruption and I have no apologies for it.

When it come to other political activities, the Rwandan people have the verdict. When millions of Rwandans tell you something, there is no reason for you not to believe it. If they tell you: �We are happy with what we have and what we are doing, we are doing it freely��

TIME: A much broader question. I sense in you that through your time in the RPF, then in government, you have become quite disappointed by � people.

Kagame: In a way, I expected things to be worse. I understood society very well from the beginning, I think, from long ago. That�s why I never get frustrated. Some of things that happen, however shocking, I expect them to be that way. I know people. I think I have understood this my whole life. Betrayals, lies, dishonesties.

TIME: That�s quite bleak.

Kagame: Society is like that. It�s not just here in Rwanda. People have asked me before this question of my life, before, as a soldier, as a commander, fighting battles, and my life in politics� and my simple answer is that the former, the soldier, the commander, these are extreme in a sense, they cause death, you can lose you life very easily. But on the other hand, things are predictable. They are clear-cut, you see? I tend to think this is easier to handle, to deal with, than politics, which has so many nuances, complexities, wrong turns. These are things that effect people beyond the borders. And things that if you get wrong, you can easily set the clock back. It�s very complex. You are dealing with the nitty gritty all the time, society, people, social, economic � their every way of life is effected by decisions you make, short, medium and long-term. It becomes more complex, more engaging, broader, it covers every part of life.

I think my think my kind of life has really prepared me for this. I was not meant to run away from problems. I just wanted to get up and move towards them. Not a problem at all.

These are for me more meaningful people than these people who write about human rights. I don�t think anybody in any human rights organization can claim to have contributed to human rights more than me. There is none. I have saved children, I have empowered women, I have actually fought repression and dictatorship and won over it and powered the people�. These people who talk about human rights, I don�t know what they mean. When I have enabled Rwandans to put food on the table and each can fend for themselves.

[INTERVIEW RESUMES IN KAMPALA]

TIME: How have the talks gone?

Kagame: It was a good meeting. It was a really good meeting. That the region is taking its place and managing our affairs is important. People are taking responsibility for what they should at least in principle and concept. The practice [of this] is a different issue. Here the international community just parachutes in and meddles in things they do not understand. It should start with national responsibility and governance, then regional. What happens in Congo, good or bad, relates to the region. If it�s bad, it spills over; if it�s good, it benefits us.

We were trying to create that responsibility. That�s the major problem. It has been lacking from the beginning, from when we have had the U.N. force in Congo. What are the responsibilities of this force? What did they come to do? If they came to help the country to exercise its responsibility and resolve its problems, I have not seen it. What we have is precisely the absence of responsibility and governance. It�s dangerous, the way the international community behaves. They give a false message: as if they have come in to address all the issues and the government can sit back since there is someone seemingly higher to deal with their problems. And then the international community does damage.

TIME: How much appetite did you find from African leaders here to take charge of African affairs?

Kagame: We have not got quite to where we should be with those that should have responsibility in Congo. I am not sure the government of Congo is thinking like this. Their arguments are still about how the international force should come in to fight their enemies for them. But that does not solve the problem, it only postpones it.

What has come out has been to agree to set up a community of countries, represented by the ministries of defense � Uganda, Tanzania, Congo-Brazzaville, Angola, Burundi, Rwanda and the DRC. They have to make an on-the-ground assessment, come up with a report to clear state what needs to be done � whether to have an international force or not, and if it does go there, to do what? They will report in another two weeks; and in another two weeks after that, we will have another summit. On the humanitarian situation, there is a possibility of contributing money towards that.

The region is really taking back responsibility, and that�s the best way. We remain with one problem: having a government in Congo that is more responsible, and more responsive to our problems. They want the force to monitor what is coming from Rwanda, and not even what originates in Congo and affects Rwanda. And they want the force to fight the M23 for them. That is what they are really saying.

TIME: How do you think the international community will react?

Kagame: The international community is definitely going to react negatively. They already did that. They think this is their part. We say: �You have been there for 12 years or more and we are not seeing anything. The failure is self-evident and it�s an indictment.�

The international reaction � it�s really amazing. It�s like one bloc against the other. Have they all turned critics? It�s like Ken Roth on behalf of Western countries against Rwanda. It�s madness. It�s an attitude problem. There is always this assumption: �These people do not know human rights. They do not know what is good for them.� What are human rights? Do human rights not mean something to me? Do I need somebody to educate me what my human rights are? Do I not know what it means to be free, to express yourself, to have justice, to be treated fairly? If all this is external to me, I have a serious problem. If Ken Roth is the one who feels everything for me, then he has taken away my rights. Is it not wrong to assume that we the leaders of our countries are simply violators of human rights, that we are just there to be violators of human rights? Where does it end? They think this is their territory, that they are the ones who are right and the ones who must shape things. They inflict harm too.

All my life, through the injustice that forced me into exile and to become a refugee, then another life in the liberation struggle, then another life as a government leader � for anybody to feel that they can equate all this with simply being a violator of human rights and this whole history just comes to zero, it doesn�t add up.

Source: world.time.com

September 18, 2012 No Comments

Rwanda: Manhunt underway for members of FDU�Inkingi in rural areas

On 15 September 2012, about 19:30, Mr. Anselme Mutuyimana of Rutsiro District (Nyabirasi sector, Kivugiza cell, Mukungu location) was arrested by police officers on allegations of membership in an illegal political organisation FDU-Inkingi.

Another member of our party, Ms. Leonille Gasengayire of Rutsiro District, Kivumu sector, was also taken by a police vehicle to the station for night interrogation on his political membership.

We are still investigating the night arrest of many other FDU-Inkingi members in the same area after the police were tipped off the passage of the party Secretary General, Mr. Sylvain Sibomana, in the District.

FDU-Inkingi is concerned by this alarming behaviour of police officers to put the interests of the ruling RPF above their national mission to equally protect all citizens and safeguard the rule of law.

FDU-Inkingi

Boniface Twagirimana

Interim Vice President

September 17, 2012 No Comments

Human Rights Report – DR Congo: M23 Rebels Committing War Crimes

M23 Rebels Committing War Crimes

Rwandan Officials Should Immediately Halt All Support or Face Sanctions

(Goma) � M23 rebels in eastern�Democratic Republic of Congo�are responsible for widespread war crimes, including summary executions, rapes, and forced recruitment. Thirty-three of those executed were young men and boys who tried to escape the rebels� ranks.

Rwandan officials may be complicit in war crimes through their continued military assistance to M23 forces, Human Rights Watch said. The Rwandan army has deployed its troops to eastern Congo to directly support the M23 rebels in military operations.

Human Rights Watch based its findings on interviews with 190 Congolese and Rwandan victims, family members, witnesses, local authorities, and current or former M23 fighters between May and September.

�The M23 rebels are committing a horrific trail of new atrocities in eastern Congo,� said�Anneke Van Woudenberg, senior Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. �M23 commanders should be held accountable for these crimes, and the Rwandan officials supporting these abusive commanders could face justice for aiding and abetting the crimes.�

The M23 armed group consists of soldiers who participated in a mutiny from the Congolese national army in April and May 2012. The group�s senior commanders have a well-known history of serious abuses against civilians. In June the United Nations high commissioner for human rights, Navi Pillay, identified five of the M23�s leaders as �among the worst perpetrators of human rights violations in the DRC, or in the world.� They include�Gen. Bosco Ntaganda, who is wanted on two arrest warrants by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes and crimes against humanity in Ituri district, and Col. Sultani Makenga, who is implicated in the recruitment of children and several massacres in eastern Congo.

Based on its research, Human Rights Watch documented the forced recruitment of at least 137 young men and boys in Rutshuru territory, eastern Congo, by M23 rebels since July. Most were abducted from their homes, in the market, or while walking to their farms. At least seven were under age 15.

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that at least 33 new recruits and other M23 fighters were summarily executed when they attempted to flee. Some were tied up and shot in front of other recruits as an example of the punishment they could receive.

One young recruit told Human Rights Watch, �When we were with the M23, they said [we had a choice] and could stay with them or we could die. Lots of people tried to escape. Some were found and then that was immediately their death.�

Since June, M23 fighters have deliberately killed at least 15 civilians in areas under their control, some because they were perceived to be against the rebels, Human Rights Watch said. The fighters also raped at least 46 women and girls. The youngest rape victim was eight years old. M23 fighters shot dead a 25-year-old woman who was three months pregnant because she resisted being raped. Two other women died from the wounds inflicted on them when they were raped by M23 fighters.

M23 rebels have committed abuses against civilians with horrific brutality, Human Rights Watch said. Just after midnight on July 7, 2012, M23 fighters attacked a family in the village of Chengerero. A 32-year-old woman told Human Rights Watch that the M23 fighters broke down their door, beat her 15-year-old son to death, and abducted her husband. Before leaving, the M23 fighters gang-raped her, poured fuel between her legs, and set the fuel on fire. A neighbor came to the woman�s aid after the M23 fighters left. The whereabouts of the woman�s husband remain unknown.

Local leaders, customary chiefs, journalists, human rights activists and others who spoke out against the M23�s abuses � or are known to have denounced the rebel commanders� previous abuses � have been targeted. Many received death threats and have fled to Congolese government-controlled areas.

M23 leaders deny that they or their forces have committed any crimes. In an interview with Human Rights Watch on August 8, Col. Makenga, one of the M23�s leaders, denied allegations of forced recruitment and summary executions, claiming those who joined their ranks did so voluntarily. �We recruit our brothers, not by force, but because they want to help their big brothers�. That�s their decision,� he said. �They are our little brothers, so we can�t kill them.� He described the repeated reports of forced recruitment by his forces as Congolese government propaganda.

Rwandan military officials have also continued to recruit by force or under false pretenses young men and boys, including under the age of 15, in Rwanda to augment the M23�s ranks. Recruitment of children under age 15 is a war crime and contravenes Rwandan law.

On June 4, Human Rights Watch�reported�that between 200 and 300 Rwandans were recruited in Rwanda in April and May and taken across the border to fight alongside M23 forces. Human Rights Watch has since gathered further evidence of forced recruitment in Rwanda in June, July, and August with several hundred more recruited. Based on interviews with witnesses and victims, Human Rights Watch estimates that at least 600 young men and boys have been forcibly or otherwise unlawfully recruited in Rwanda to join the M23, and possibly many more. These recruits outnumber those recruited for the M23 in Congo.

Congolese and Rwandans, including local authorities, who live near the Rwanda-Congo border told Human Rights Watch that they saw frequent troop movements of Rwandan soldiers in and out of Congo in June, July, and August in apparent support of M23 rebels. They said that Rwandan army soldiers frequently used the footpath near Njerima hill in Rwanda, close to Karisimbi volcano, to cross the border.

In addition to deploying reinforcements and recruits to support military operations, Rwandan military officials have been providing important military support to the M23 rebels, including weapons, ammunition, and training, Human Rights Watch said. This makes Rwanda a party to the conflict.

�The Rwandan government�s repeated denials that its military officials provide support for the abusive M23 rebels beggars belief,� Van Woudenberg said. �The United Nations Security Council should sanction M23 leaders, as well as Rwandan officials who are helping them, for serious rights abuses.�

The armed conflict in eastern Congo is bound by international humanitarian law, or the laws of war, including Common Article 3 and Protocol II to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, which prohibit summary executions, rape, forced recruitment, and other abuses. Serious laws-of-war violations committed deliberately or recklessly are war crimes. Commanders may be criminally responsible for war crimes by their forces if they knew or should have known about such crimes and failed to prevent them or punish those responsible.

A United Nations Group of Experts that monitors the arms embargo and sanctions violations in Congo independently presented compelling evidence of Rwandan support to the M23 rebels. Its findings were published in a 48-page addendum to the Group�s interim report in June 2012. The Rwandan government has denied these allegations. The UN sanctions committee should immediately seek additional information on M23 leaders and Rwandan military officers named by the Group of Experts with a view to adopting targeted sanctions against them, Human Rights Watch said.

In July and August, five donor governments � the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden � announced the suspension or delay of assistance to Rwanda in light of the evidence presented by the Group of Experts. Although Rwandan military support for the M23, and M23 abuses have continued unabated, on September 4 the United Kingdom Department for International Development announced it would disburse around half the assistance it had withheld.

The renewed hostilities by the M23, the Congolese army, and various other armed groups have resulted in the displacement of over 220,000 civilians who have fled their homes to seek safety elsewhere in Congo or across the border in Uganda and Rwanda.

�Congolese civilians have endured the brunt of wartime abuses,� Van Woudenberg said. �The UN and its member states should urgently step up their efforts to protect civilians, and donor governments providing aid or military assistance to Rwanda should urgently review their programs to ensure they are not fueling serious human rights abuses.�

Background on the M23 and Its Leadership

The soldiers who took part in a mutiny from the Congolese army between late March and May and formed the M23 group were previously members of the National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP), a former Rwanda-backed rebel group that integrated into the Congolese army in January 2009.

General Ntaganda led the mutiny following Congolese government attempts to weaken his control and increased calls for his arrest and surrender to the ICC, in accordance with Congo�s legal obligations to cooperate with the court. He was joined by an estimated 300 to 600 troops in Masisi territory, North Kivu province. Ntaganda�s forces were defeated by the Congolese army, which pushed the rebels out of Masisi in early May. Around the same time, Col. Makenga, a former colleague of Ntaganda in the CNDP, announced he was beginning a separate mutiny in Rutshuru territory. In the days that followed, Ntaganda and his forces joined Makenga.

The new armed group called itself the M23. The soldiers claimed their mutiny was to protest the Congolese government�s failure to fully implement the March 23, 2009, peace agreement (hence the name M23), which had integrated them into the Congolese army.

Some of the M23�s senior commanders have well-known histories of serious abuses, committed over the past decade in eastern Congo as they moved from one armed group to another, including ethnic massacres,�recruitment of children, mass rape,�killings, abductions, and torture. Before the mutinies, at least five of the current M23 leaders were on a UN blacklist of people with whom they would not collaborate due to their human rights records.

Ntaganda has been wanted by the ICC since 2006 for recruiting and using child soldiers in Ituri district in northeastern Congo in 2002 and 2003. In July, the court issued a second warrant against him for war crimes and crimes against humanity, namely murder, persecution based on ethnic grounds, rape, sexual slavery, and pillaging, also in connection with his activities in Ituri. On September 4, the ICC renewed its request to the Congolese government to arrest Ntaganda immediately and transfer him to The Hague. Human Rights Watch has documented�numerous war crimes�and crimes against humanity by troops under Ntaganda�s command since he moved from Ituri to North Kivu in 2006.

According to research by UN human rights investigators and Human Rights Watch, Col. Makenga is responsible for recruiting children and for several massacres in eastern Congo; Col. Innocent Zimurinda is responsible for ethnic massacres at Kiwanja, Shalio, and Buramba, as well as rape, torture, and child recruitment; Col. Baudouin Ngaruye is responsible for a massacre at Shalio, child recruitment, rape, and other attacks on civilians; and Col. Innocent Kayna is responsible for ethnic massacres in Ituri and child recruitment.

Ntaganda and Zimurinda are also both on a UN Security Council sanctions list. Under the UN sanctions, all UN member states, including Rwanda, are obligated to �take the necessary measures to prevent the entry into or transit through their territories of all persons� on the sanctions list. Both Ntaganda and Zimurinda have traveled to Rwanda since April, former M23 fighters who accompanied Ntaganda and people present during meetings Zimurinda attended in Rwanda told Human Rights Watch.

Publicly, the M23 maintains that Ntaganda is not part of its movement. However, several dozen former and current M23 fighters and others close to the M23�s leadership told Human Rights Watch that Ntaganda has played a key command and leadership role among the M23 rebels, operating from the Runyoni area, and that he participated regularly in meetings with the M23�s high command and Rwandan army officers.